William Dargue A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y

Ladywood, Ladywood Green

B16 - Grid reference SP055865

St Mary Wood: first record 1552, Lady Wood 1565

Woodland was a valuable economic resource in the Middle Ages. Woods provided timber for building, and pollarded or coppiced trees gave an endless supply of wood for laths, fences and, crucially, firewood. Well-managed woods could generate a substantial income for the tenant and the owner. This district is named after the Lady Wood which lay between Monument Lane and Ladywood Brook and stretched from Portland Road to Spring Hill.

The wood may have been church property or perhaps its income was dedicated to the church. The chapel of the medieval Priory of St Thomas in Bull Street was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and it may be that the wood belonged to the Priory. The first record of Lady Wood so-named is in 1565 by which time the wood had long gone and it was remembered only by a fieldname. It was also recorded some years earlier as pasture land by the name of St Mary Wood Field and the erstwhile property of the Guild of the Holy Cross.

Photograph above of Alexandra Street taken in 1967. This street, which no longer exists, ran parallel to and south of Anderton Street in north Ladywood. This image, 'All Rights Reserved', is from the BirminghamLives website and is reused here with the kind permission of Professor Carl Chinn.

The Guild was founded by wealthy benefactors who set up almshouses, paid for the town midwife and were responsible for the upkeep of some of the roads and bridges in the town. They also paid for two chantry priests at St Martin's-in-the-Bull Ring and maintained a chiming clock at their Guild Hall in New Street. St Mary Wood was one of the fields whose income funded the guild's charitable activities. After the dissolution of religious guilds under Henry VIII, the Guild Hall became the King Edward VI Grammar School and a number of former holdings including St Mary Wood were granted to the school on its establishment in 1552.

North-west of the town, between Ladywood Middleway and Monument Road, Icknield Street and Great Hampton Street, lay the medieval open fields of Birmingham manor, though their exact location and

extent is unknown. From Anglo-Saxon times the village was dependent for its self-sufficiency on this land. However, the fact that this is not especially fertile soil may help to explain why the

market venture in Birmingham was developed by Peter de Birmingham, the lord of the manor as early as 1166. The open fields were enclosed early, probably before 1300.

The Great Plague of 1665 was believed by Birmingham's first historian William Hutton to have come to the town from London in a box of clothes which was brought by a carrier who

stayed at the White Hart Inn in Digbeth. The disease would have spread rapidly in the densely built-up town. Plague houses were marked with a red cross and the victims were allegedly buried

outside the town on wasteland at Ladywood Green which lay between Ladywood Middleway and Monument Road.

The site was later known as the Pest Ground or the Pest Heath. However, when it was developed for housing in the mid-19th century no evidence of burials was reported. Neither has evidence been found in local parish registers of a sudden increase in the death rate in 1665. Hutton was writing over a hundred years after the event and his account may record a memory of one of many earlier outbreaks in 1631 or 1637, for instance. It may be that the route of the 1665 plague followed Watling Street and by-passed Birmingham.

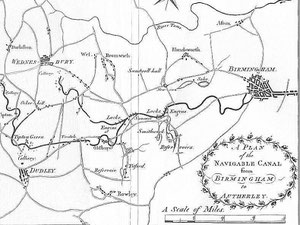

The Birmingham Canal

Take a look at Birmingham's first canal as it cuts its way through Ladywood. The cutting of the Birmingham'canal followed the success in

1761 of James Brindley's first canal which was made to transport the Duke of Bridgewater's coal to Manchester, and subsequently the Trent & Mersey and Staffordshire & Worcestershire

canals. Despite improvements in the road system following the introduction of the turnpikes, importing coal to fuel the town's industries was expensive and slow. Furthermore Birmingham was some

distance from a navigable river.

Birmingham businessmen believed that raw materials and manufactured goods could be better moved by canal. Brindley was asked to draw up plans to connect Birmingham to the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal near Wolverhampton with a branch to the Wednesbury coalfields. The section to Wednesbury opened in 1769 and the canal was an immediate success. The arrival of the first boat-load of coal at Friday Street (now Summer Row) immediately brought the cost down from 13 shillings per ton to just 7 shillings. By 1772 the canal had reached Wolverhampton and shortly afterwards gained access to the ports of Bristol, Liverpool and Hull.

Although the canal now terminates at Gas Street Basin, its first terminus was at Paradise Street on the site of Alpha Tower. The wharves became a vast coal depot with over 60 merchants based here

until the railways took the trade away.

Arthur Young in his Tours in England & Wales wrote of a visit he made to Birmingham in 1791:

The capital improvement wrought since I was here before is the canal to Oxford, Coventry, Wolverhampton, &c.; the port, as it may be called, or double head canal in the town crowded with coal barges is a noble spectacle, with that prodigious animation, wit the immense trade of this place could alone give. I looked around me with amazement at the change effected in twelve years; so great that this place may now probably be reckoned, with justice, the first manufacturing town in the world.

From this port and these quays you may now go by water to Hull, Liverpool, Bristol, Oxford, and London. . . Coals before these canals were made, were 6d. [d = pre-decimal pence] per cwt [hundredweight]. At Birmingham, now 41/2d. The consumption is about 200,000 tons a year, which exhausts about 20 or 22 acres; it employs 40 boats, each 20 ton a day for the six summer months.

Click to enlarge the maps below.

Because Brindley had followed the 450-foot contour (c75m) to avoid the expense of building locks, the canal's route meandered considerably with a number of sharp turns. Thomas Telford reported on the canal's condition in 1824, some 50 years after its opening:

Where it enters Birmingham, it has become little more than a crooked ditch with scarcely the appearance of a haling-path, the horses frequently sliding and staggering in the water, the haling-lines sweeping the ground into the canal, and the entanglement at the meeting of boats being incessant. Whilst at the locks at each end of the summit at Smethwick, crowds of boatmen are always quarrelling or offering premiums for a preference of passage, and the mine-owners, injured by the delay, are loud in their just complaints.

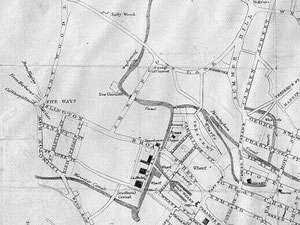

Telford took less than two years to upgrade the canal, completing work in 1838 from Old Turning Junction, between Sheepcote Street and King Edwards Road, to make a wider, more direct and faster

route by digging cuttings and building aqueducts.

Take a look. The New Main Line was built over 10m wide with towpaths on each side and the sides lined with brick. It first cuts through the loops of the Birmingham Canal Old Main Line and then runs parallel to it but at a lower level. The distance to Wolverhampton was reduced from 36km to 25km via 24 locks. Telford's elegant cast-iron bridges are a notable feature.

The Old Main Line was widened or left as loops all of which are still navigable, though some have no towpath: Oozells Loop, Icknield Port or Rotton Park Loop and Winson Green Loop (aka. Soho Loop). The New Main Line by-passes Icknield Port Loop which is used as a feeder from Edgbaston Reservoir. On Icknield Port Road the stables, covered dock, superintendent's office, workshop, stores and crane at British Waterways Maintenance Depot all remain.

Old Turn Junction/ Deep Cutting Junction is now recognised as the crossroads of the English canal system. The railway from New Street station to Wolverhampton runs directly underneath the canal here where an unusual roundabout was installed during World War 2 so that the canals could be blocked off separately in case of bombing.

Take a look. The Roundhouse at the corner of St Vincent Street and Sheepcote Street is an interesting building, not least for its unusual and distinctive horseshoe shape. It

was built in 1840 for the London & North Western Railway as a mineral and coal wharf on the canal.

With the advent of the railways from 1838 canal use began to decline nationally, though in the West Midlands agreements with the Birmingham Canal Navigations and the London & North Western Railway resulted in the construction of a number of canal-rail interchanges. Goods were frequently carried locally by canal to be carried further afield by rail. The tonnage carried actually increased towards the end of the 19th century against the national trend which saw canal use decline steadily.

In 1831 Salford Reservoir, located alongside Spaghetti junction, introduced the beginnings of a piped water supply for Birmingham. Water was pumped from there to the reservoir at Monument Road in Ladywood between Waterworks Road and Reservoir Road. From there it was gravity fed to consumers. As the town continued to expand, so did the demand for piped water. To enable water to be gravity fed to a wider area of distribution, by 1853 water was being pumped to a new higher-level reservoir off the Hagley Road east of Meadow Road.

Take a look. The design of the tall gothic Edgbaston Pumphouse with its italianate boilerhouse chimney was entrusted to Martin & Chamberlain, a Birmingham partnership well-known

for their fine gothic school architecture in the city. J R R Tolkien lived at a number of addresses near here, and it is believed that Perrotts Folly and the chimney of the Pumphouse were his

inspiration for the Two Towers in 'The Lord of the Rings'.

Perrotts Folly or The Monument in Waterworks Road is c30m high. With 139 steps to the top it was built in red brick with 6 storeys as a gothic viewing tower in 1758 by John Perrott on his country estate, the old manorial park of Rotton Park. The tower is octagonal and has pointed gothic-style windows; the top storey is embattled. Perrott lived at the rebuilt Rotton Park Lodge at the junction of Gillott Road and Rotton Park Road. After his death in 1766 his grandson sold off the estate which was subsequently built on with housing. The folly was used from 1884 as one of the world's first weather stations by Abraham Follet Osler, inventor of the self-regulating wind gauge, and as the Midland Institute weather observatory until 1984. A successful public appeal was made 1958 for its repair. This is a Grade II* Listed building which is regularly open to the public.

Click the images below to enlarge.

Take a look at St John's Church.

The church of St John the Evangelist on Monument Road was built on the site of Ladywood House on land leased from King Edward VI School. Consecrated in 1854 the small decorated gothic-style church by

S S Teulon was greatly enlarged with the addition in the same style of a chancel, aisles and transepts in 1881 by Birmingham architect J A Chatwin. Chatwin's chancel has an ornate roof, mosaic floor

and carved choir stalls.

The church is rich in memorials. An interesting one in the nave, which depicts a three-funnelled warship, is inscribed:

To the Glory of God and in memory of Walter Grounds, Petty officer, H.M.S. Terrible. An exemplary sailor, a good Son and the best big gunshot in the British navy. Died Hong Kong, June second 1902.

As well as the Victorian commemorative stained glass are late 20th-century trefoil windows by Kim Jarvis depicting Ladywood and the Caribbean community.

There is good woodwork here: in the Lady Chapel a fine altar of 1927, commemorative wood carvings at the end of each pew depicting the four Apostles; a handsome oak screen along the passageway to

the vestry.

The ornate gothic stone pulpit with its carved saints is dated 1881, the brass lectern 1890. The pews of the north transept were removed in 1993 creating a flexible area for services, displays and meetings. Hanging lanterns on either side of the main aisle were given by Canon & Mrs Norman Power, in memory of their son Michael who drowned in a sailing accident. There is a single chiming bell in the tower.

Until Victorian times Ladywood was an agricultural area on the fringes of Birmingham. It saw sporadic development in the late 18th century as a high-class retreat close to town. But from the 1840s the district was developed extensively for housing from as Birmingham spread outwards.

At the north end of Ladywood the area around King Edwards Road was land sold by the King Edward VI Schools Foundation. By 1841 there was a population of c9000 which rose to c43 000 by 1871. And by 1888 Ladywood was completely built up with working-class housing as far west as Edgbaston Reservoir, as far north as Spring Hill and Summer Hill, and as far south as the Hagley Road.

By 1906 building from Bearwood and Smethwick was closing in from the west, although much of Rotton Park still remained open countryside. By the beginning of the 20th century Ladywood had become a

district of long straight streets of closely packed terraces, behind which gloomy courts of back-to-backs housed a large population in squalid conditions. This Victorian housing was completely

replaced during the 1960s and 1970s.

After World War 2 Ladywood was designated a Redevelopment Area. Decayed housing and industry was cleared wholesale and much of the former street pattern was changed. All of Ladywood and surrounding inner-city areas were largely rebuilt from the 1960s in a mixture of tower blocks and later low-rise housing. At the end of the 20th century some of the early 1960s developments have been again redeveloped.

See Newtown for more information on inner-city post-war redevelopment.

The photographs below are by Phyllis Nicklin's and were taken as the north end of Ladywood was being demolished and rebuilt. See Acknowledgements - Keith Berry. Click to enlarge.

Left to right: Shakespeare Road awaiting demolition photographed in 1968; Anderton Road near Shakespeare Road demolished; and maisonettes being built in Browning Street in 1957. Browning Street has recently been rebuilt again.

William Dargue 09.04.2009/ 14.10.2012